|

"...suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died and was buried. He Descended to the dead"

Read: Matt27:32-61

Last week we looked at the dual nature of Christ – fully God and fully man.

This week we move on to think about some of the best known scenes in the life of Christ, the time from his trial to his death. As we do so we’ll consider the theological meaning and importance behind these various events and reflect on what this means in our day to day life of faith.

He suffered under Pontius Pilate

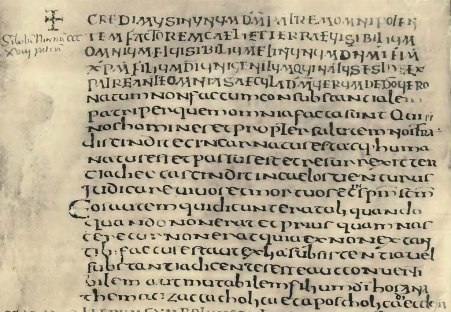

Having made reference to his nature and described him as Gods Son and our Lord, the creed now moves forward and chronicles the key events in Jesus life. That it does so is important. The creed is not simply a list of spiritual truths, it is also contains historical facts which anchor the Christian faith to a series of actual events and people.

Rev Prof Alister McGrath quotes the fifth century writer Rufinus as saying:

“Those who handed down the Creed showed great wisdom in emphasizing the actual date at which these things happened, so that there might be no chance of any uncertainty or vagueness upsetting the stability of the tradition”

Without this anchor to a series of historical events the gospel would be a fairy tale, a story, albeit with great meaning and importance, but a story that happened long ago, and a story that through it’s lack of historical content would be open to massive re-interpretation and creative embellishment over the ages.

The actual historic happenings and goings-on in the life of Jesus are central to the Christian faith. That this is so in-turn underlines something else of great importance, namely that the physical and the spiritual are inextricably linked. God operates in history, in space and time, in the created order. We all live in space and time, and in re-iterating Gods work in history we affirm that God has entered the realm of our existence and has set to work here.

In doing so we affirm that the Christian faith is not just about ideas, but is, to quote McGrath again “…about God acting, and continuing to act in history”.

Reflect and pray: It is easy to speak of faith as a purely ‘spiritual’ thing. To see it as primarily existing in the realm of ideas and theory, and as an ‘otherworldy’ thing. It is easy to forget that the Christian faith is firmly anchored in the here and now and has a strong sense of down-to-earth realism about it.

As you reflect on your life of faith do you see a tendency to be ‘other-worldy’ or ‘this-worldy’ in your focus? Do you see the things of God as being primarily located in the heavenly realms or in the space and time that we inhabit?

What difference does this make to our life of faith?

With this in mind let’s reflect on the suffering of Christ under Pilate

Jesus Christ, the saviour, the one ‘through whom all things were created’ the ‘light of world’ who despite being it’s author and saviour, his creation did not recognize. The tragedy of the situation, the full horror of this neglect and ignorance and willful turning away is remembered as Jesus’ final few days begin to unfold.

In this short line ‘he suffered under Pontius Pilate’ the two worlds of the symbolic and the immediate collide. Pilate as well as playing a very real part in the actual sufferings of Christ and his condemnation, also represents the whole world and its willful ignorance and refusal to see Christ for who he was – the whole of creation unable to recognize its creator – such is the effect of the sin that corrupts creation.

In this event then we see a deep truth about the world illustrated and made shockingly clear. We see the place from which creation and mankind needs rescue – the place of rejection of its God and creator. The good news is built upon this realization, that the sin which pervades creation is so damaging that it comes close to destroying our ability to recognize and respond to God when he comes among us.

This corruption is given a particular name by theologians. It’s called ‘original sin’. Original sin has many interpretations and is clouded in some distinctly un-helpful ideas but is perhaps best understood not as a “metaphysical curse hanging over the human race” a disease that all are born with, but as a description of the tangle in which we live and our tendency to look first to ourselves rather than to God. This is the sin described in the metaphor of the Garden of Eden as Eve takes the apple and this is the tendency under which we all still live. Rowan Williams offers an interesting and helpful comment on this often mis-understood idea on page 82 -83 in his book Tokens of Trust.

This corruption to which all of creation is bound is so deeply rooted that without help we are incapable of breaking its hold. The gospel message is that help came, and as the creed continues the full cost of this help becomes heartbreaking clear. We’ll go on to think about this in a few moments, but why not take some time now to pause, think and pray?

Reflect and pray: It’s easy to think of sin lightly, or to think of it as nothing more than the fairly minor things that one gets wrong each day. But to do so is to misunderstand the seriousness of sin and its scope. The sin which the scriptures speak of is less about the small daily failings which are symptoms of something more serious, and is more about the underlying and inherent tendency within mankind to ‘go his own way’, to reject and refuse to acknowledge his creator. Sin in this sense is something which none are exempt from.

Spend a short while bringing to mind this tendency to refuse to acknowledge God in our lives. Bring to mind some of the ways in which this is manifest.

Now either individually or together pray this prayer of confession together:

Almighty God, our heavenly Father,

We have sinned against you and against our neighbour in thought and word and deed,

Through negligence, through weakness, through our own deliberate fault.

We are truly sorry and repent of all our sin.

For the sake of your Son Jesus Christ, who died for us,

Forgive us all that is past and grant that we may serve you in newness of life to the glory of your name.

Amen

Before we go on to pray the absolution together we’re going to spend some time thinking about the continuing unfolding of events that make possible the forgiveness that we receive.

“…was crucified, died, and was buried…”

We are all familiar with the horrors of the cross and so we’ll not go into them here. Instead we will explore the meaning of the cross, its symbolism, and its importance.

Against the backdrop of Pilates’ rejection of Jesus and refusal to acknowledge him as God – representative of humanity as a whole – the full consequences of such a course of action now become painfully clear. Such a decision on Pilates part, and on the part of humanity as a whole can lead mankind to one place and one place only – the place of death.

But instead of Pilate as an individual and as a representative of humanity going to the place of death at the hands of God, it is God who goes to the place of death at the hands of Pilate / mankind. The fate that is deserved by humanity for forsaking its creator is taken by the creator on behalf of those who have turned away from him. Where mankind should be we find God instead.

The Apostle Paul says just this - that Christ ‘became sin’ and that in doing so he takes on himself the curse that we bring upon ourselves. (To explore this more fully see 2Cor5:21 and Gal3:13)

The New Testament writers employ several pictures and analogies to describe what is happening on the cross. Although these are well known to us it might be helpful to unpack them and use them as a starting point for a response of praise and worship.

Sacrifice: Jesus death on the cross can be described as a sacrifice in the mould of the Old Testament sacrifices – an offering that makes peace with God, offered because the peace has been shattered by human action and sin. Jesus is the blood sacrifice required to restore peace with God, and unlike a lamb or other such animal, the sacrifice of Christ offered once and for all makes possible a lasting peace.

Ransom: Jesus death on the cross can also be described as a ransom in the sense that Jesus life is the price paid to set mankind free – in this case from sin and its consequence death. Jesus life is ‘paid’ to the powers that oppress, sin, death, and the powers of destruction in order to purchase our freedom.

Substitution: Jesus death on the cross can be described as a substitution in so far as he takes the place of the guilty (mankind) and suffers on our behalf what we ought to suffer ourselves. In taking this suffering and punishment upon himself, and standing in our place, we are relieved of the need to do so ourselves.

Reflect and give thanks: It is easy enough to lose the ‘first love’ that we had for God. The ‘first love’ that move us to a place of unrestrained praise as we realized the lengths to which Christ went to draw us to himself and wash us clean from our sin, and heal us of our brokenness. As walk through the journey of life and faith, what we have been rescued from seems to get further and further away. We’ve explored afresh the significance of Christ’s sacrifice upon the cross and in light of this it’s appropriate to respond in praise and thanksgiving. So why not spend some time doing this now. You might want to sing a hymn or song, or you might want to have a time of open prayer, or even pray a well known prayer together. Whichever way you choose, spend some time praising God, thanking him for all that Christ did and the new life which it brings.

He descended to the dead

As we come to the end of the session for this week we come to a line in the creed that has caused a great deal of confusion to modern Christians, a line about which we may reasonably ask ‘what does it mean’?

We have already asserted that Christ died on the cross, that he was not spared the awfulness of death and that he endured to the very end. So why, having said all of this did the writers of the creed feel the need to say ‘he descended to the dead’ – surely this is what happens to all who die?

The original meaning of the line was not quite that ‘he descended into hell’ – i.e the place of separation from God. The wording actually means that he descended into the ‘places beneath’ and in the words of Rowan Williams “…referred to a passage in the Letter to the Ephesians about Jesus descending to the lowest parts of creation as well as ascending to the heights…”(Eph4:10) so that he might ‘fill all things’. This has its origins in the ancient Jewish idea that the souls of those who had died resided in underground prisons. 1Peter3:18-19, although notoriously difficult to understand might suggest something along these lines. The usual interpretation of this line of the Creed has been that Christ descended to the place of the dead, specifically to preach to the Faithful Jews who had died before Christ’s coming. This interpretation goes on to suggest that those who have died before Christ’s coming have the chance to hear the good news and be transformed by it. This is not to advocate a ‘second chance after death’ theology (which has recently been made popular by Rob Bell in his book ‘Love Wins’) but it is to say that the redemptive benefits of Christ’s death might be applied to those who lived faithfully with God before the incarnation as well as those who responded to Christ in the incarnation.

The idea of a prison for the souls of the dead may be unfamiliar to us, and possibly sound quite strange. It is a reminder that the Creed was written at a point in time in which the imagery used to understand and give meaning to life in the world was very different to our own. However an important point might still be made, namely that the work of Christ on the cross is so very powerful and all encompassing that even those who lived before him have the chance to benefit from his redeeming actions. The good news is that Christ has ‘filled all things’.

It’s important to say that this is by no means the only interpretation of these verses in 1Peter and the line in the Creed and some more conservative theologians would probably disagree with this reading. There have been numerous other attempts made to interpret this scripture and through it this line in the creed. The Reformers for example preferred the idea that the ‘descent into hell’ described the suffering of Christ on the cross, the pain of death and the breaking of communion with the Father – the descent is given a psychological interpretation – but ultimately there is no more or less scriptural evidence for this interpretation than any other.

But it is worth thinking about this. As those who live post-Christ it’s easy to see how his redeeming work affects us and we sometimes paint a narrow picture of the remit of this redemptive work – but the benefits of the cross, although located in time and space, are not bound by them. Perhaps in thinking about this line of the creed we’re challenged to enlarge our understanding of the scope and remit of Christ’s redemptive action.

Moving on to yet another interpretation of this line, we find ourselves in more comfortable territory. The line also makes another important statement, that Jesus really did die. He wasn’t spared the horror of death because of his status as God incarnate, Jesus divinity did not compromise his humanity – he was raised from the place of. What he experienced in death is what all experience in death, and it was from this real physical death that he was raised. But more on that next week.

Reflect, pray, and worship: As we come to the end of this weeks session we’ve covered a great deal of ground. Much of it will have been very familiar and a simple re-iteration of the most basic theology of the suffering, crucifixion, and death of Christ. Although well known, there is I believe, a great deal to be gained in meditating on these historical goings on. We remind ourselves that our faith is rooted in actual events, rooted in history, and is not merely the creation of a collection of spiritual imaginings. We remind ourselves of the reality of the suffering of our Lord and the lengths to which he went to win our salvation.

In the face of this we are humbled, we are thankful, and we respond in praise and worship. The cost of our salvation was not a theory, or an idea, but a life.

And it is in this God that we trust. The God who entered our realm, who lived in our time and space, and who underwent genuine suffering on our behalf. We can trust a God who is prepared to take on himself so much for our sakes.

|